Strands

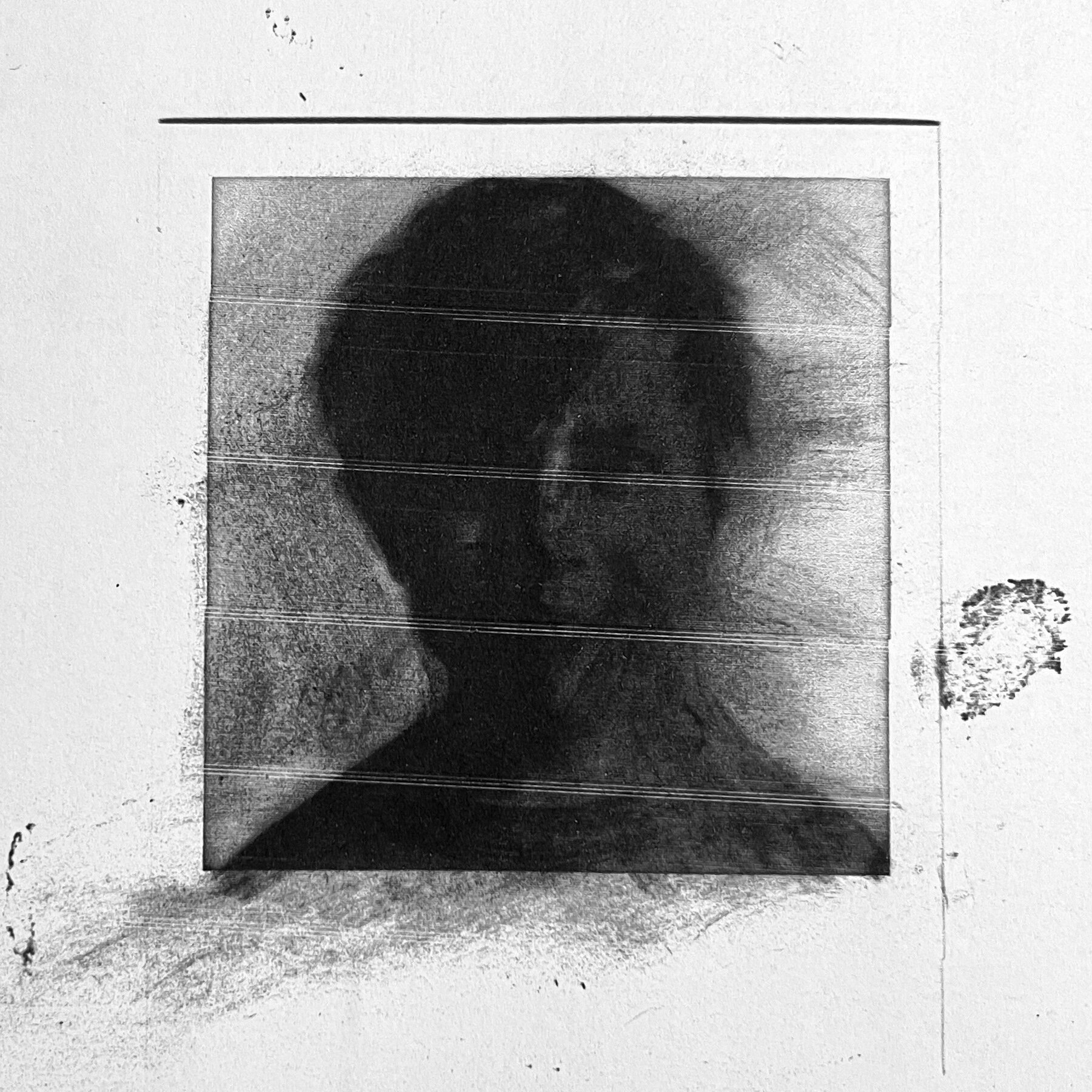

In a large envelope, shoved tightly into the mailbox of my New York City apartment building, were the immigration records of my late grandmother. The photocopied paperwork included a list of all known displaced persons camps she resided in Germany after WWII, as well as the oldest known photograph of her, completely obscured to black, the shape of her hair deeply familiar. Over a decade later I’d visit her homeland of Poland with little information about her past. I’d visit Auschwitz on a Monday, having witnessed a fatal car accident along the way. And I’d stand in a room facing a large glass enclosure that was once filled with the hair of the victims at the death camp, only a fraction of which remains.

In the years since seeing my grandmother’s picture and my experiences in Poland, I’ve come to study my own children relentlessly. I try to memorize their ever-changing shapes, the scent of their hair, the hum of their voices. These thread-like locks that emerge from their scalps have captivated me since their births. For my series Strands, I bedim their faces on scanned polaroids with ashes burned from clippings of their hair. Then I repeatedly photocopy each of their images, until they are almost indistinguishable from each other. Do I still know them? Am I still able to tell them apart? What persists?